More than 130 million cell phones in the US alone are retired every year, the USGS estimates. Not great news for the planet, considering phones contain substances harmful to humans and the environment, like cadmium, lead, and beryllium (all carcinogins), as well as arsenic. So what's the best way to make sure your old phone's not leaking chemicals into the ground?

What use is an old smartphone?

Smartphones contain all manner of recyclable materials, but they also represent a small fraction of a much larger picture. Discarded consumer electronics – from refrigerators and monitors to lamps and toasters – represent a literal gold mine of materials to be harvested.

The amount of gold hidden in the e-waste generated worldwide in 2014 was roughly 300 tonnes, which is equal to 11 percent of the global gold production from mines in 2013. But gold is only one of a number of valuable materials and precious metals to be found in electronic goods – there is also a wealth of plastic, iron, copper, aluminum, silver, palladium and platinum.

The 41.8 million tonnes of e-waste created worldwide in 2014 was estimated to be worth around $44 billion.

Who’s recycling?

The US accounted for almost 17 percent of global e-waste generated worldwide in 2014, amassing 7.1 million tonnes of discarded electronics.

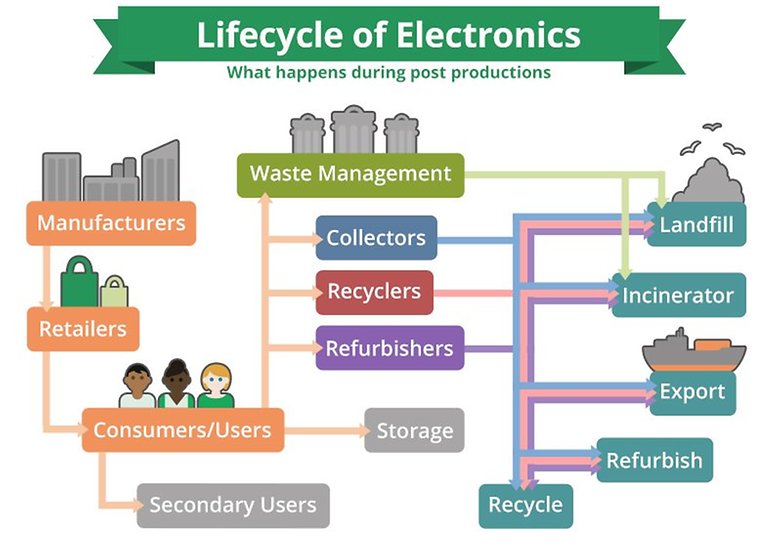

There are four different ways this waste is dealt with:

- Official take-back systems, which ensure local and environmentally-friendly recycling

- Disposal in mixed residential waste; meaning it is either incinerated or dumped in a landfill

- Collection outside of official take-back systems – through private companies – who trade it freely (including exporting it to developing countries)

- Informal collection, resulting in export to, and recycling in, developing countries

Of the 7.1 millions tonnes of e-waste generated in the US in 2014, it is estimated that between 12 and 15 percent was collected through official take-back systems to be recycled through state-of-the-art facilities. No official figures account for exactly what happened to the remaining 85-88 percent, but it was undoubtedly a mix of the remaining three options, with anywhere between 50 and 80 percent of the e-waste collected for recycling in the US ultimately being exported.

Note: all figures in the preceding sections comes from this United Nations University report.

Why export e-waste?

Generally speaking, it is more profitable to export e-waste than it is to recycle it in state-of-the-art facilities.

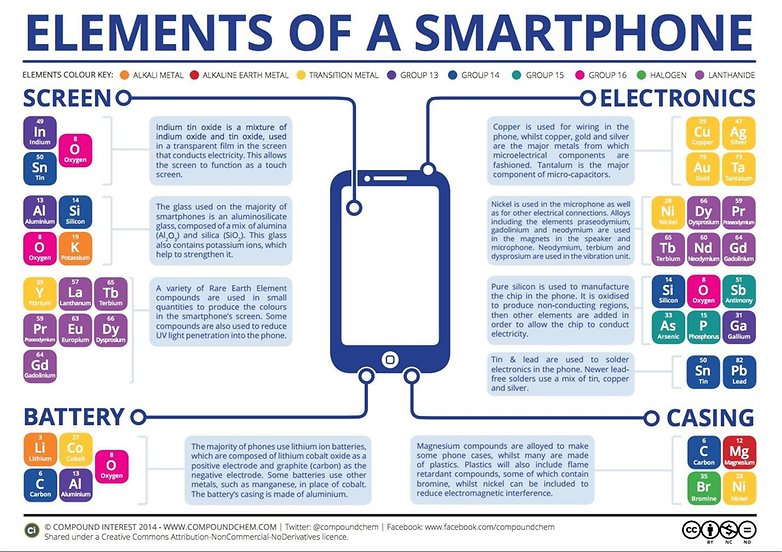

Consumer electronics not only contain valuable materials, they also come laden with hazardous materials, and the two must be separated. Up to 60 elements from the periodic table can found in complex electronics, and these include toxic heavy metals, such as mercury, lead and cadmium, and chemicals, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and flame retardants, which can release highly toxic dioxins when burned.

In their various forms, these hazardous materials can cause damage to the central nervous system, kidneys, brain and to developing fetuses, and many are recognized carcinogens or produce them when burned.

To handle this waste requires either high-tech facilities or people willing to expose themselves and their environment to the immense risks. The latter option is cheaper and readily available in developing countries. Indeed, if you work in the business, exporting e-waste often pays twice: you get paid to take the waste off people’s hands and again to export it.

In 1989, the Basel Convention was born. This international treaty was designed to place limitations on how developed nations export hazardous waste to less developed countries. An amendment was made to the treaty in 1994, proposing a total ban on the export of hazardous waste from more developed nations to less developed ones. At the moment, the US and Haiti are the only two nations, out of a total of 183, not to have ratified the amendment. The EU has fully implemented the Basel Ban into its Waste Shipment Regulation, making it legally binding for all member states. The US, however, retains lackluster e-waste disposal legislation.

Despite an increasing amount of state legislation on the subject, the only federal legislation to date is the Resource Conservation Recovery Act (RCRA), which is profoundly punctured by loopholes and exemptions, all but encouraging the export of hazardous e-waste, which primarily ends up in developing countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa.

What happens abroad?

The developing world is littered with the unfortunate evidence of unchecked e-waste recycling.

In India, there is no legislation overseeing how e-waste is handled. This results in 95 percent of the hazardous materials coming into the country being sorted and recycled in urban slums.

The methods of recycling e-waste in these environments are rudimentary and often conducted by children. Acid baths are used to strip heavy metals from circuit boards, and components are burned in the open, producing toxic fumes. When recovering precious metals from e-waste, the residual acid and toxic heavy metals are left out in the open to seep into the soil, groundwater and air, or dumped in nearby rivers, contaminating the environment for years to come.

Most major wireless carriers participate in "take-back" programs, which allow you to send your dead phone back where it came from for free—or sometimes even a cash rebate. Once a cell phone arrives at a take-back facility, if it's still workable and a relatively recent model, it's likely going to get refurbished and resold, either on the consumer market or to a charity. (Verizon's HopeLine program, for example, donates phones loaded with 3,000 free minutes to domestic violence victims.) Other refurbished phones are sold in Latin America and Africa, to people who don't mind using a secondhand, behind-the-times phone.

If your phone is really kaput, it will either get broken down and sold for parts or passed on to a smelter, where the entire phone is melted down and the liquids are separated to be reconstituted. (This process is sometimes called "above-ground mining.") Smelters harvest the little bits of valuable metals (gold, copper, iron, silver, zinc, nickel, platinum, tin) used in the circuitboards and soldering. In one metric ton of old cell phones without batteries (about 8,800 individual phones), there's an estimated 308 pounds of copper, 7 pounds of silver, and half a pound of gold. The smelting process, also used to melt down recycled aluminum cans, does generate some greenhouse gases and slag (the discarded silica and metal oxides used to isolate liquid metal). But overall, the environmental and monetary costs of smelting down existing metals are lower than mining, transporting, and refining new ore. For example, one ton of gold ore only contains .18 ounces of pure gold, while there's about 40 times that amount in one ton of cell-phone circuitry.

Breaking cell phones up and separating the parts is the process that most people are leery of. Annie Leonard points out that workers in China and Africa often dismantle electronics' harmful insides without proper personal or environmental protection: For example, in the town of Guiyu, China, 1.5 million pounds of e-waste are dismantled every year—often by workers without gloves—and leftover junk is disposed of in open fires.

Unfortunately, there's no easy way to find out if your cell-phone carrier exports items abroad to be broken, because many of them work with third-party companies—three of which I tried unsuccessfully to contact by, um, telephone. (I did reach a T-Mobile rep who said his company works with a Dallas-based recycler called Touchstone that separates phone components in the US. He also said 70 percent of the phones T-Mobile receives go on to be refurbished.) Newer phones like smart phones may be heavier than old candy-bar-style phones, but they contain a lot more electronics in a smaller package.

The good news: Cell phones are getting more environmentally friendly. Today's phones are made with considerably less cadmium and lead than older models, and they're also getting lighter. The average phone weighs around 4 ounces, minus the battery—about half of what it weighed in 2000. Recycling rates are also improving: In 2003, fewer than 1 percent of owners recycled their phones, but now it's closer to 20 percent. Rep. Gene Green (D-Texas) recently introduced the Responsible Electronics Recycling Act (H.R. 6252). It would outlaw sending e-waste to developing nations, but it's still hanging out with the House Committee of Energy and Commerce.

You can help minimize waste by opting for a refurbished phone (available through all major carriers) instead of a new one. Once you're done with your phone, there are a number of recycling systems you can participate in. To reduce the carbon footprint from ground transportation and reclamation, I prefer programs that handle large volumes of cell phones. Best Buy has kiosks in nearly every store where you can drop off your used electronics. The program doesn't export any non-working phones or components to developing countries, and it requires third-party partners to submit documentation of environmental compliance. If you're looking to make a few bucks off your phone, check out GreenPhone.com, which gives you cash for your old unit; offers you a free, printable shipping label; and will plant a tree every time you recycle a phone. The folks over at Earth911 recommend this website to see if your local recycling outfit is certified as an "e-Steward"—whichrequires strict control over exporting overseas, "full accountability for the entire downstream recycling chain," and disclosure on any airborne toxins released during the smelting process. If none of these float your boat, you can see an extensive list of drop-off and mail-in recycling programs at the EPA's eCycle site.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét